If you want a physical manifestation of Britain’s unquestioning acceptance of oligarchs and its refusal to examine the origin of their wealth, you need to take a walk past Harrods towards the Victoria and Albert Museum.

After about 200 metres, you will see on the right-hand side of the road the unmistakable burgundy glazed tiles of a tube station. That is your destination. You can’t get on the underground here, because the station stopped accepting passengers decades ago and became a Ministry of Defence office. But it still has the platforms and shafts of a tube station, and that’s why it came to the attention of a former banker called Ajit Chambers in 2009. Chambers had a plan, which he revealed at one of the public events that Boris Johnson used to hold when he was the mayor of London.

Chambers told Johnson that he had identified 40 disused London underground stations, and he wanted to transform them into tourist attractions. “San Francisco has Alcatraz; Paris has its catacombs,” he said. “I have a proposal. I have been trying to get it to TfL.”

Johnson jumped in. “It is brilliant. I love it,” he said. “London underground. OK, we are going underground.” TfL – Transport for London, which oversees the capital’s trains, buses, taxis, trams and other modes of public transport – is one of the few bodies run by the mayor, so this was something Johnson could theoretically do something about. He promised that his staff would evaluate the proposal and follow up.

There were a few obstacles to Chambers’s plan. For one thing, although dozens of stations have been closed over the years, there aren’t 40 actual ghost stations in the sense of places you could walk into and convert into something new. Most have been demolished. For another thing, the ghost stations that do exist are still stations, packed with power lines and machinery and – at platform level – speeding trains.

Still, if anyone was going to make a go of breathing life back into the ghosts it was Chambers, who was almost comically persistent. He took to haunting Johnson’s public events, and his appearances became so predictable that a columnist at the Times called him “London’s foremost Boris-botherer”. City Hall officials would try to kill off Chambers’s idea on the grounds of health, safety, cost or something else, only for Johnson to bring it back to life by discussing it at public events.

Chambers argued that the most promising place to trial his idea was that station on the Brompton Road, which was closed in the 1930s due to lack of passengers. His vision for the site involved holographic passengers in period dress at platform level, a rooftop bar and an event space in the old ticket hall. Chambers managed to put on a handful of proof-of-concept events in the station, and people who attended them still excitedly describe the thrill of descending the old stairs to platform level, of seeing a huge map dating from when this was an anti-aircraft command post in the second world war, of the sign saying “Danger: ammunition”.

By 2013, it seemed as if Chambers’s persistence had won through. The fact that events were successfully held at Brompton Road suggested that Chambers’s vision of this as a future tourist attraction was not so far-fetched. It might even have been possible to make a decent profit from it. All he needed was for public officials to sign over the lease, and those years of Boris-bothering would have paid off. But that is where the plan fell apart.

The true obstacle to Chambers’s plan was not health and safety legislation or even doubts over profitability. To hand over the old Brompton Road station to Chambers, the government department that owned it – which, since the second world war had been the Ministry of Defence – would have had to overcome the reflex to sell things to the highest bidder, whoever they are and whatever their intentions. Chambers claimed to have raised £25m to back his project, but as it turned out, that wouldn’t even have bought half of the ghost on Brompton Road when it did finally change hands in early 2014.

That sale was the final act in a remarkable tale that demonstrates how Britain is prepared to welcome anybody to its shores, no questions asked, if the price is right. When the government was asked to choose between helping an entrepreneur to realise an eccentric dream that would enrich its capital city in a unique way or selling an asset to the highest bidder, there was only going to be one winner, and it wasn’t going to be Chambers.

Instead, the winner was a man named Dmitry Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch who was widely seen as helping to restore Russian influence over his homeland after a popular uprising in 2004 A man who the FBI was investigating prior to his arrival in the UK and continued to investigate in the years that followed. In choosing to make the UK his second home, Firtash had picked wisely. He was welcomed with open arms – by politicians, by Cambridge University, and even by royalty.

To understand how Firtash got so rich that he could buy a tube station, we need to go back to the days of the cold war, when the Communist party still wielded unchecked power over Russia and the other Soviet republics.

By the 70s, the Soviet Union, which had been seen as a great economic rival of the west in the years after the second world war, was falling rapidly behind. However, the USSR did have one thing that the west lacked: vast quantities of natural gas, which it used to power its factories, heat its homes and earn valuable dollars as exports to the west.

This abundance of gas – controlled by the country’s first state-run corporation, Gazprom – helped stitch the Soviet economy together, and nowhere more so than in Ukraine, which was a centre of heavy industry second only to Russia. Ukraine’s factories and chemical works were dependent on pipelines bringing fuel from the same distant Russian and central Asian gas fields that exported gas to Europe. Thanks to this subsidised source of energy, the factories could compete with their rivals, and millions of Ukrainians had stable, well-paid jobs.

And then, in 1991, everything changed. The Soviet Union collapsed. Ukraine became independent and suddenly went from being an energy-rich country to being energy-poor. Its factories were only viable because of cheap natural gas, and it had hardly any gas of its own. Without its factories, its people would have no work; if its people had no work, its economy would collapse. Logically, one of two things should then have happened. Ukraine should either have rapidly become far more efficient in its use of gas, closing the hungrier industries, finding new ways to earn a living, so its imports and exports could balance each other, or it should have been essentially reabsorbed into Russia. The first option was economically ruinous; the second option was politically inconceivable.

Fortunately, the need to reach an immediate decision was postponed by the fact that Russia also relied on gas. Its economy survived thanks to the hard currency it earned by exporting gas to Europe, and almost all those exports passed through Ukraine. That meant that if Ukraine couldn’t pay its gas bills, it could just steal it from the pipelines that ran through its territory, and Russia couldn’t turn off the taps without also cutting off its high-paying customers farther west.

It is well established that large reserves of oil or gas almost invariably corrupt countries, and this is what happened in Ukraine. But this corruption derived not from controlling the gas, but from controlling the pipelines that moved it, and thus the ability to reward supporters with valuable shipments, or export licences. This wasn’t so much rent-seeking behaviour as toll-seeking.

Insiders in Russia and Ukraine teamed up to create shady intermediary companies that took gas from Gazprom at the Russian border, sold it to high-paying Europeans, and split the proceeds. Often, they paid for the gas not with money but with goods, and barter transactions added a layer of opacity to the deals, which made them even harder for ordinary citizens to understand. Nothing did more to corrupt Ukraine or to maintain its dependence on Moscow than its politicians’ addiction to this money. Russia added the cost of the stolen gas to Ukraine’s bill, but the insiders didn’t care, since they were allowed to keep the profits.

When Vladimir Putin became Russian president in 2000, however, he decided that – at least at the Russian end – this wealth machine needed to be brought in house. If anyone was going to get rich from exporting gas, it was going to be him and his friends, not Gazprom managers and their shady enablers. It took him a little while to wrestle the old guard out of the door, but eventually he had a loyalist in charge of the gas giant. There would still be an intermediary company between Russia and Ukraine, so the money flows would remain hidden, but that company would be half-owned by Gazprom to ensure Putin got his share. Its name was RosUkrEnergo (RUE), and it took over gas supplies between the two countries in July 2004.

That was a big year in Ukraine. In the autumn, the prime minister, a thug called Viktor Yanukovich who was heavily backed by Putin, tried to win the presidency by rigging an election. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians took to the streets of Kyiv, waving the orange flags of Yanukovich’s rival Viktor Yushchenko. After weeks of continuous protests, the election was reheld and Yanukovich lost. For many young Ukrainians this moment – known as the Orange Revolution – was a glorious expression of how ordinary people can triumph over the corrupting influence of oligarchs and their money.

For Putin, however, who had spent time and money backing Yanukovich, Ukraine’s revolution was a personal humiliation. But he had a useful way to remind Ukrainians – and any other countries tempted to follow Ukraine’s lead – why humiliating the Kremlin was a bad idea. Gazprom told the post-revolutionary government it would be renegotiating its gas supply contract, and when Ukraine refused to agree to its terms, cut it off.

In the depths of winter, the whole country suddenly realised quite how dependent it was on Russian goodwill. In some parts of Ukraine it was -30C. Those kinds of temperatures kill, so it was really no choice at all. Yushchenko capitulated and signed the new deal with RUE, a humiliation that split the coalition that had powered the revolution, and from which his reputation never recovered. RUE was already doing well under the old contract, and now the money really started to flow.

“Only one source of power proved to be stronger than the Orange Revolution,” wrote the scholar of international relations, Margarita M Balmaceda. “Not (former) PM Viktor Yanukovich, not Russia, but the power of energy-related interests.”

But who were those interests? Who actually were the owners of RUE? Everyone knew that Gazprom owned half of the company, but who owned the other half?

The owner of the other half of RUE, it turned out, was a 39-year-old Ukrainian man named Dmitry Firtash. According to the accounts he gave, he started out in business selling food to central Asia, but when his customers failed to pay their bills, he accepted payment in gas, which he sold at a profit in Europe. It was in this complex barter trade that he learned the skills required to run RUE.

It never became entirely clear why Putin’s Kremlin should have selected Firtash in particular to be its chosen partner in Kyiv, as opposed to one of Ukraine’s better-known oligarchs. Journalists reported his alleged links to a notorious Russian mobster Semyon Mogilevich, which might perhaps explain it, but he denied there were direct business ties between them.

Thanks to his alliance with Gazprom and by extension with Putin, Firtash had gained extraordinary wealth and power. He was the Kremlin’s man in Ukraine, a gas-fuelled kingmaker. In his home country, Firtash became a controversial figure, accused of restoring Russia’s influence over their homeland. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that he started looking around for a foreign country where he might buy a second home. He chose the UK.

I contacted Firtash to ask why he had settled on the UK, but received no answer to this, or indeed to any of the other questions I sent over via his UK partner Robert Shetler-Jones. What we know for sure is that in the years after his big gas coup, Firtash hired a lobbying company, Asquith & Granovski, to help burnish his image in the UK. The company, run by a Ukrainian spin doctor, Vladimir Granovski, and a British aristocrat and former spy, Raymond Asquith, served wealthy ex-Soviet citizens looking to engage with the UK.

In February 2007, a limited company – the British Ukrainian Society (BUS) – was incorporated. Granovski and Asquith became directors, along with Firtash’s right-hand man, Shetler-Jones, plus a Conservative MP called Richard Spring who provided Asquith & Granovski with advice on “political, economic and current affairs matters” in exchange for £35,000-40,000 a year. The society was headquartered in Knightsbridge. “Are we trying to improve our reputation? Of course,” Firtash later told the Wall Street Journal. “I can’t just be the place where people throw darts.”

Another MP, a Labour backbencher called John Grogan, worked closely with the BUS. He’d become interested in Ukraine after being inspired by the Orange Revolution, and he chaired an all-party parliamentary group on the country. “I was slightly naive perhaps. At that stage I wasn’t aware of the funding arrangements,” he told me.

I asked Grogan what he thought Firtash was trying to do by supporting the British Ukrainian Society. Grogan said the model was the British Syrian Society, which had been established in 2002 by Bashar al-Assad’s father-in-law to help build links between London and Damascus and which also had Spring on the board. The BUS’s founding documents laid out objectives that were almost word for word the same as those of its Syrian counterpart.

In 2008, in his capacity as chair of the BUS, Spring secured a parliamentary debate on Ukraine, which is the kind of thing that makes any organisation look influential. In the debate he talked at length about how Britain’s interests lay in a democratic, western-oriented Ukraine free of the taint of corruption. “I suppose reputationally the kind of things the BUS did were in themselves pretty harmless – cultural events or lectures or whatever,” said Grogan. “No doubt, Firtash was trying to gain friends and influence. I have no idea if he personally met the people involved.”

It doesn’t cost much money to fund a lobbying group, and Firtash’s associates looked around for other projects, which is what took them to a dinner in 2007 in memory of the composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky at Cambridge University. According to a source with knowledge of the negotiations that followed, one of the speakers at the event mentioned that the Ukrainian language was not taught at the university, which seems to have inspired a new project for the oligarch. “Some of these British representatives associated with Firtash approached the organisers of the dinner and asked how much they would need to have Ukrainian taught in one way or another,” the source said.

A mutually acceptable total was agreed, and the university’s Slavic department organised language classes for anyone who wanted to learn Ukrainian. “That was where the first few thousand quid came from. Though whether that was actually Dmitry Firtash’s money, I don’t know. I think it was,” the source told me.

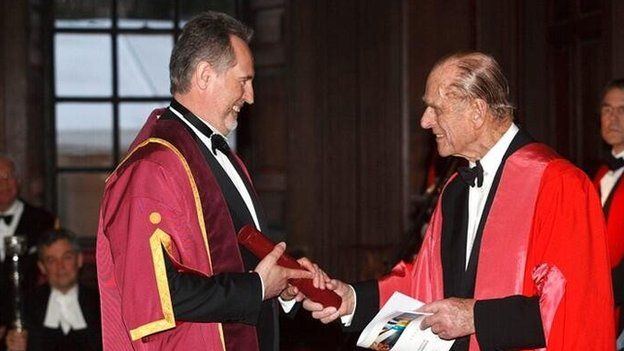

In early 2008, the DF Foundation was created with the aim of funding education about Ukraine and giving scholarships to students. In 2010, Cambridge University created a formal Ukrainian Studies course thanks to a donation from Firtash of £4m. In March 2011, Firtash was welcomed into Cambridge’s prestigious Guild of Benefactors, a club for its most generous donors, by none other than the Duke of Edinburgh.

Firtash was busy elsewhere, too: he grouped all his businesses into one holding company based in the British Virgin Islands. According to later analysis by Reuters, he was able to earn $3bn just by reselling the gas that Gazprom sold him, thanks to receiving it at an artificially low price. With billions of dollars more in loans from Gazprombank – which made him the Russian bank’s largest single borrower – he expanded fast into fertiliser, titanium, banking and the media. He had funded Yanukovich’s successful political comeback – the former prime minister won the 2010 presidential election – so had an ally running his homeland, and thanks to his philanthropy he had met the husband of the queen of his adopted second home. Everything he touched was turning to gold.

From 2011, Firtash took to visiting Cambridge quite often, meeting the students whose scholarships he was paying for and bringing along a television crew to record him doing so. The University of Cambridge gave him a special medal – containing nearly 500g of sterling silver, designed by Jane McAdam Freud and individually numbered – for his outstanding philanthropy.

In 2012, Firtash bought himself a London residence, a mansion just down the road from Harrods built by the luxury developer Mike Spink which, according to a property publication, cost something in the region of £60m. With this London base, his infiltration of the British establishment became even more ambitious.

Towards the end of 2013, he agreed another donation to Cambridge University and, in a series of events called the Days of Ukraine, opened trading on the London Stock Exchange and visited parliament with his wife, where he was greeted by the Speaker at the time, John Bercow. In a photograph of the occasion, Bercow and Firtash are shaking hands, while Lord Risby – as Richard Spring has been known since he was elevated to the House of Lords in 2010 – leans slightly forward in the background, with the kind of rapt smile you might see on the face of a proud father watching his son pick his way through a piano recital.

Back at home, however, Ukraine was entering a turbulent time. Firtash had helped Yanukovich become president in 2010 but over time, Yanukovich’s corruption became ever more blatant. He even started building a huge palace on the outskirts of Kyiv. In 2013, when Yanukovich announced he would end integration with the European Union and instead align Ukraine with Russia, it proved the final indignity. Protests swelled over subsequent months into another revolution, and, in February 2014, Yanukovich fled to Russia, while Moscow sent troops to seize the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. This was the beginning of the conflict that has escalated so horribly in the past month.

If Firtash was concerned by this turn of events, he did not show it. In February 2014, as the British government scrambled to make sense of what was happening in Ukraine, the oligarch was invited into the Foreign Office. According to a later statement in parliament, matters of national security were not discussed. However, according to a report by a Russian news agency, Firtash said that he had “tried to persuade them that imposing sanctions against Russia was a bad idea.” He added: “That will only make things worse. America provoked Putin into this situation.”

Even this wasn’t quite the high-water mark of Firtash’s influence in Britain. That came three days later, when his purchase of the Brompton Road tube station for £53m from the MoD was finalised, and Ajit Chambers’s business dream was destroyed. The ghost station directly adjoined Firtash’s London property, and it’s not hard to imagine that he would have loathed Chambers’s plan to create a rooftop bar and restaurant. Late-night revellers would have had a view straight down into his back garden.

Firtash seems to have lacked any equivalent vision of his own for the site, however. The government’s press release announcing the sale made much of the station’s history and the unique features, but Firtash showed no sign of being interested in either aspect. “The whole underground station thing isn’t really that interesting,” the developer Mike Spink, who advised Firtash on the sale, wrote to me by email. “In reality, it’s just another prime central London site.”

Britain had provided Firtash with a luxury home, welcomed him into the establishment’s bosom, awarded him a medal, showered him with attention from members of both houses of parliament, sold him a central London landmark and asked him to come in and share some thoughts with the Foreign Office. In return it got money for a major university, extra cash for members of parliament, support for its property developers and millions of pounds straight into the state budget in exchange for an old tube station that the MoD wasn’t even using much.

Criticising Britain for this may seem a little unfair. After all, the argument goes, any country would have welcomed Firtash’s money and expertise, so it would have been self-defeating to turn it away, right?

This is a troubling argument. Firtash was Putin’s man in Ukraine, and yet Britain integrated him so enthusiastically into the establishment that he advised the government on Putin’s invasion. Should it really be talking to a man like this? Or accepting his money? Or selling him a property with access to the London underground system? Or, indeed anything at all?

“This has clear implications for national security,” noted parliament’s Foreign Affairs committee in 2018 about the tendency to invite Kremlin-aligned oligarchs to buy what they liked in the UK. “Turning a blind eye to London’s role in hiding the proceedings of Kremlin-connected corruption risks signalling that the UK is not serious about confronting the full spectrum of President Putin’s offensive measures.”

There are certainly plenty of other western countries that have helped Firtash transform himself. Cyprus, Hungary and Switzerland sold him his shell companies; Austria provided him with a bank account; ex-politicians from all over Europe have been happy to hitch their names to his various foundations. But other countries behaving badly is no reason for Britain to do so, too, not least because Firtash’s integration went so much further in the UK than it did elsewhere.

And the response of the US to his activities provides a fascinating contrast to what happened in the UK.

In 2003, the FBI indicted Semyon Mogilevich, a Moscow-based gangster, and added him to the list of its Top 10 most wanted. Mogilevich was accused of a lengthy list of crimes, including money laundering, racketeering, fraud and more. As it investigated Mogilevich’s dealings and associates, it started to look into gas shipments through Ukraine, and inevitably its attention fell on Firtash.

In April 2006, just months after Firtash’s big gas deal helped doom the prospect of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, the Wall Street Journal announced that US law enforcement was investigating RUE’s ties to organised crime. The WSJ reported that Asquith had gone to Washington on Firtash’s behalf to deny any connection to Mogilevich, which is a denial that Firtash has had to make on a regular basis ever since. “There is no business connection between Mr Mogilevich and me. I have never had any direct business dealings with him, nor does he have any interests in any of my companies,” Firtash told the WSJ in 2007. According to an account of a meeting between Firtash and US officials a year later, and released by WikiLeaks: “Firtash acknowledged that he needed, and received, permission from Mogilevich when he established various businesses, but he denied any close relationship with him.” (After the cable was published, Firtash issued a statement denying he had ever acknowledged this, and suggested the claim was a “mistranslation or misunderstanding”.)

None of this lobbying succeeded in persuading US officials to stop investigating him, however. While members of the British parliament took Firtash’s money, the US embassy in Kyiv kept cabling its suspicions about what he was up to, and FBI agents kept following them up. “Given Firtash’s swift ascent from failing canned foods company manager to multi-billionaire gas magnate, he might still be beholden to the forces that helped him rise so quickly,” one cable noted laconically, after Firtash bought himself a bank.

Eventually they had enough evidence to convince a grand jury to approve an indictment. On 12 March 2014, Austrian police officers arrested Firtash in Vienna at the FBI’s request. It was exactly a fortnight after the final approval of his purchase of the Brompton Road station from the British government.

Prosecutors accused Firtash of having bribed officials in India with more than $18.5m in order to gain access to titanium resources, which in turn he was planning to sell to Boeing. The aircraft giant’s corporate headquarters is in Chicago, and the FBI’s Illinois office was investigating. The indictment showed that the alleged scheme dated back to April 2006, and had continued for years.

Firtash fought back hard, posting bail of €125m and issuing a statement to condemn the indictment as absurd. He was being targeted for political reasons, he said, in order to allow US officials to cement their influence over his homeland’s new post-revolutionary government. “I will not allow my reputation to be ruined by those who are driven by political motivations and are not interested in Ukraine and its people,” he said in a line that was repeated in every interview he and his associates gave. Firtash was ably assisted by Tim Bell, the veteran British PR magnate behind the now defunct company, Bell Pottinger.

Apart from bland denials of such accusations, US officials were unable to respond, since they could not risk undermining their case, which is why a person with knowledge of the case was only prepared to discuss it with me anonymously. This source insisted that since the indictment had been sealed in June 2013, long before Ukrainians rose against their president, any suggestion of political motivation was ridiculous. The long delay in issuing the arrest warrant had been entirely a result of waiting for Firtash to fly to a country that might be prepared to extradite him. When he arrived in Austria, they made their move.

For a little while, despite his arrest, Firtash’s absorption into British high society continued. In mid-March, Cambridge held a ceremony to welcome his wife, Lada Firtash, into its Guild of Benefactors, but press coverage was hostile, and protesters greeted her car as it arrived at the venue. The university announced that it would only spend the most recent donation from the Firtashes if he was acquitted. It also promised to improve checks on the provenance of donations. The MoD was also challenged over why it had been prepared to sell him the Brompton Road ghost station, and similarly struggled to answer.

In parliament a minister explained that “all funds were paid to the MoD through UK regulated solicitors, in accordance with normal practice, to ensure that appropriate financial checks were made on their client”. The fact that US authorities were investigating Firtash’s companies had been reported in the press years previously, so this was not a convincing argument. The British government’s focus had been on making as much money as possible, and it had actually subcontracted its checks on the origin of that money to Firtash’s own lawyers while ignoring anything that stood in the way of closing the sale. It wasn’t a good look, and it left the MPs and peers who had so willingly accepted the money with some explaining to do.

Many of the details about what Firtash has done in the UK are known thanks to Helen Goodman, a Labour MP until 2019, who became the party’s expert on Ukraine. She said that parliamentarians involved in the British Ukrainian Society had offered to pay for her to go to Kyiv, saying the money came from “somebody in oil and gas”, but she turned the offer down and arranged her own transport. “It was just obvious that Firtash was corrupting Ukrainian politics, and equally clear that Firtash has an agenda,” she told me. “The thing seemed to stink. Every aspect of it seemed really weird.”

Asquith did not respond to my many emails or phone calls, and neither did Lord Risby. One parliamentarian involved in the British Ukrainian Society did agree to talk to me, provided I didn’t identify them in any way, but seemed ignorant about the fact that Firtash was involved in creating the society. “You might say I’m a bit of a useful idiot, but this didn’t occur to me,” the individual said.

A politician who was prepared to talk to me on the record was the Conservative MP John Whittingdale. He did not end his connection to the BUS until long after Firtash’s arrest and accepted more than £3,000 in donations to fund a trip to a 2015 conference held in Vienna and addressed by Firtash. A contemporary statement on Firtash’s website made much of the fact that Whittingdale had attended. I asked Whittingdale – who at the time of our conversation was culture minister in the UK government, but at the time of the conference was just a backbench MP – whether he was concerned that his involvement had given Firtash a degree of credibility that he otherwise would have lacked.

“Do you think so? I’m not sure that it gives him much credibility. Goodness, one meets a lot of people. Just meeting them I don’t think enables them to claim any credit. I was briefly director of the British Ukrainian Society, but it is very much an arm’s length operation,” he said. “I am aware of the support for Oxford university, or Cambridge, whichever it is. That’s a matter for them … We are a free society, and as long as it’s legal, it’s up to them.”

And the tube station? Wasn’t he worried about potentially tainted money being used to buy property from the British government? “That’s not a bribe or anything, it’s a commercial transaction,” he said. “I am dimly aware that he did buy a tube station somewhere in west London to turn it into a property or something, I don’t know the detail at all. At the moment he’s sitting in Austria somewhere, but there are much more dodgy–” he stopped and appeared to reconsider what he was about to say. “If Ukrainians come and produce evidence for instance that his money had been illegally acquired, or stolen from the people, then obviously that would be something we should look into, and if proven then take action over. But as far as I’m aware they haven’t, and there are plenty of other oligarchs who have money in London … Nobody in Ukraine has ever expressed any concern about this.”

That last remark stayed with me because it was so at variance with my own experience. I have reported on Ukraine for years, and many people I have spoken to have expressed concern about Britain giving a safe haven to oligarchs and their money. Whittingdale said Ukrainian prosecutors would have to win a case against Firtash if they wanted Britain to act, but those prosecutors are so demoralised, corrupted and out-resourced that such a victory is an impossible dream. Even if they do bring a prosecution, cases from other countries show that the oligarch concerned would simply argue that the proceedings were politically motivated and claim asylum in the west. If an oligarch is not prosecuted, Britain doesn’t investigate; if the oligarch is prosecuted, Britain doesn’t investigate either. The fact that a government minister fails to acknowledge this “heads they win, tails we lose” injustice helps explain why Britain has consistently failed to interrogate the origins of suspect wealth.

At present, Firtash is still in Vienna and still battling extradition to the US. His extradition hearings have bounced between courts, with different Austrian judges ruling different ways, while in Chicago his US-based lawyers have sought to have the whole case thrown out. A number of US citizens have happily taken Firtash’s money to lobby on his behalf, but prosecutors are sticking to their task and still hope he’ll arrive in Chicago eventually.

Britain, meanwhile, is failing to seize the assets of Putin’s oligarchs, to the incredulity of its allies in Europe and the US. What they need to understand is that this failure is not the fruit of a political decision, but of a decades-long policy to accept money without asking where it came from. Britain literally lacks the mechanisms to do what politicians suddenly want to do. If we want this to change, we will need to build the state capacity – and the political will – from the ground up.

Adapted from Butler to the World: How Britain Became the Servant of Oligarchs, Tax Dodgers, Kleptocrats and Criminals, which will be published by Profile Books on 10 March. To order a copy, go to the guardianbookshop