London, 16 March 2022

by Anthony Robinson

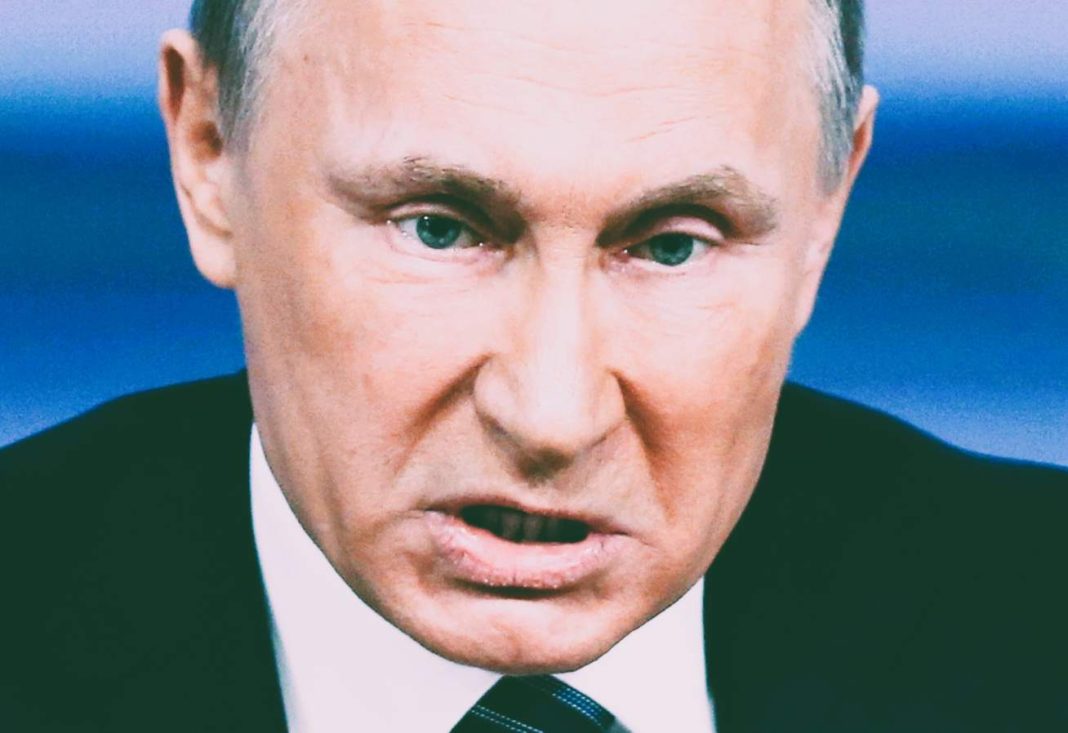

Seldom has the warning that “Russia is never as strong as it seems, or as weak” been so apposite as the events in Ukraine unfold. Just before the invasion order Putin held a mighty parade of his soldiers and their shiny equipment in Red Square, just like Germany’s Kaiser Bill playing with his toy soldiers before the outbreak of the first World War.

Three weeks later it appears that brave resistance by the Ukrainian army and, above all by an engaged and determined civil society, is put paid to Putin’s expectations of a “short victorious war” followed by capitulation, occupation and regime change. But an invasion which has been planned for years is only beginning and no-one should under estimate the ruthlessness and cruelty which the Russian military command has demonstrated on so many occasions.

As with that other fascist, Hitler, Putin’s hubris will lead to nemesis. The question is – how soon, and by what means?

Not only has Putin under-estimated the strength of the Ukrainian resistance, he – together with me and probably you and many other observers – also under-estimated the ability of supine “western” governments to find the backbone to swiftly put into place painful sanctions and re-arm.

Putin’s regime is more brittle than the Soviet regime. Even if Putin does subdue Ukraine the cost of even partial occupation will be crippling. And, as Talleyrand noted in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna “you can do anything with bayonets – except sit on them.”

There is of course a risk that, like Hitler, Putin personally would be prepared to fight to the bitter end, which in this case would mean breaching the nuclear weapons use taboo. Failing that truly terrible prospect, I doubt that Putin could long survive the prospect of prolonged bloody civil war with Russia’s fellow Slav neighbours made worse by unexpectedly savage western sanctions.

In an ideal world some brave soul would arrest Putin, or shoot him – before he causes maximum damage and kills many thousands. But no-one had the courage to get rid of Stalin – and Stauffenberg tried to kill Hitler but fluffed it. Khruschev, a far less murderous figure, however, was overthrown by politburo insiders, who branded him “a hare-brained schemer”. Putin is a more dangerous, Stalin-type figure. A failed coup would be fatal for its protagonists.

But the way in which Putin publicly humiliated Sergei Naryshkin, his chief foreign spymaster, for initially describing invasion as “possibly the worst outcome” and the glum look on the faces of people as diverse as Sergei Shoigu, his main military link, when told to prepare for nuclear war, and Elvira Nabiulina, Russia’s central bank governor, when confronted with massive sanctions, suggests deep unhappiness with their now clearly delusional “man of destiny.”

Given the uber-Czar like concentration of power in Putin’s hands, the absence of any clear institutional path for a succession, the strength of the Siloviki and the weakness of Russian civil society, the forced removal of Putin would leave a massive and dangerous vacuum of power in Moscow – and an unpredictable “dog fight under the carpet” for the transfer of power.

It would be better for Putin to be removed before Ukraine is wrecked, the sooner the better. We in the West should be thinking hard NOW about what sort of a relationship we would like to have with a post-Putin Russia and what a new Russian regime would have to do to justify Russia’s return to the international community. The main unknown – what would be the reaction of the Siloviki to an insider coup – and especially the commanders of the vast army now committed to a short victorious war?

The author is the former Moscow bureau chief of the Financial Times and writes for aej.org.