Marek Edelman and the Warsaw Ghetto: “Do not die with your head bowed down”

The Warsaw Ghetto uprising began 80 years ago. Memories of ex-commander Marek Edelman, who was one of the very few survivors. He was interviewed before his death by AEJ Hon. President Otmar Lahodynshy for profil magazine.

by Otmar Lahodynsky, Die Furche, April 12, 2023

On the morning of April 19, 1943, heavily armed SS units and German police forces marched into the Warsaw Ghetto. They were to transport the rest of the remaining inhabitants to the Nazi extermination camps. But they were to be surprised by grenades and rifle shots and pushed back to the ghetto walls on the very first day of the unequal fight.

There were several hundred fighters from the Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB), as the Jewish Combat Organisation called itself. It had organised the resistance against the Nazi troops – with bunkers, weapons caches, and ambushes. As early as January 1943 the fighters had stopped the deportation of ghetto residents to Nazi death camps through armed actions. Through contacts with the Polish underground army Armia Krajowa (Polish Home Army), the fighters aquired weapons, mainly rifles, pistols, and explosives.

So in April 2,000 SS men as well as police officers under the command of SS Brigadeführer and Police General Jürgen Stroop entered the ghetto for an evacuation scheduled for only three days. Stroop wanted to give Adolf Hitler a birthday present by liquidating the last remnants of the Jewish quarter. But he met with unexpected resistance. Under the command of the 21-year-old fishmonger’s son Mordechaj Anielewicz, the Jewish fighters delivered a fierce house-to-house fight to the German troops.

During the weeks of fighting, SS troops systematically burned down all the blocks in the ghetto. Against the overwhelming power of the Germans, who were supported by artillery and tanks, the ŻOB fighters eventually stood no chance. But it took four weeks, until May 16, for the ghetto to be completely destroyed. On that day the SS demolished the large synagogue in the ghetto as a symbolic action. Over 50,000 ghetto residents and resistance fighters had been killed or transported to Nazi murder camps. Stroop triumphantly telegraphed to his superiors: “The former Jewish residential district of Warsaw no longer exists.”

Only a few Jewish fighters survived by escaping from the ghetto through the sewers. One of them was Marek Edelman, then 22, who worked as a hospital messenger in the ghetto. He never felt like a hero, he explained when interviewed by the author of this article in 1988. “At that time it was about not letting yourself be slaughtered. All that mattered was to shoot. You had to show that. Not to the Germans, they could do it better, but to the rest of the non-German world we had to show that.”

Their struggle was also an attempt to die differently than the Nazi mass murderers had planned, he said. “Not with your head down and your eyes closed, but with your head up and the will to live in freedom and dignity.” As a messenger from the ghetto hospital, Edelman had previously witnessed how the Nazi occupiers, starting in 1940, first crammed half a million Jews into the ghetto in Warsaw and from there progressively herded them onto cattle-trucks bound for the death camps.

That this went smoothly for a long time was also due to the perfidious Nazi propaganda. In July 1942 posters announced to the half-starved ghetto population that every volunteer to be resettled in an alleged labor camp would receive three kilogrammes of bread and one kilo of jam. Why should one distribute bread if one wanted to kill them, as numerous reports about the gas chambers pointed out. “And hunger veiled everything with the thought of three brown, freshly-baked, loaves of bread,” said Dr Edelman.

From the transshipment point where the death trains departed, Edelman fetched important people from the columns to take them to the hospital. The SS didn’t transport sick people anywhere for a long time in order to keep up the appearance of trips to a labour camp. The fact that he was able to save those who were about to die was what prompted him to study medicine after the war, he explained. He had led 40 men to the brush factory premises.

“People always thought that shooting was the greatest heroism,” he said. “We just shot there” – with the few weapons that the “Aryan side” could smuggle in. And the resistance fighters were afraid that their struggle would not be noticed on the other side of the wall. “We saw a carousel and people, we heard music, and we were terrified that the music would drown us out,” he told me.

On May 8, 1943, the Germans discovered the bunker in which Mordechai Anielewicz was holed up with his staff. Before the SS invaded, they all committed suicide. Only Edelman and a few other ghetto fighters managed to escape through the sewers from the burning ruins.

A new political home

The end of the war did not leave him in a mood of victory. He studied medicine and later became a cardiologist in Łódź. After the Communists eliminated the Polish Socialist Party in 1948, Marek Edelman lost his political home, which he only found again after 1980 in the independent trade union Solidarność.

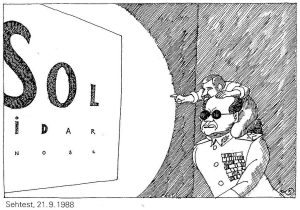

Edelman was interned after the imposition of martial law by General Wojciech Jaruzelski in December 1981. He later boycotted the commemorations organised by the Commmunist regime for the 40th and 45th anniversaries of the Uprising. Edelman thought little of the philosemitic course of the then ruling Polish government. “It’s easy to love someone who is no longer there,” he said contemptuously.

Lifelong obligation

But the Poles had not been any more anti-Semitic than other peoples. In Warsaw, 12,000 Jews had been hidden from the Nazis by Poles, despite the threat of a death penalty. “One in 10 Poles was involved in helping Jews in some way,” Edelman thought. “That’s not a bad ratio.”

The Germans were to be easier to deal with for the Polish Communists who ruled after 1945. Jürgen Stroop was extradited to Poland after his conviction at the Nuremberg war  crimes trial and executed there in 1952. Ostpolitik under Chancellor Willy Brandt led to a normalisation of German-Polish relations in the early 1970s. During a visit to Warsaw in 1970, Brandt knelt in front of the Ghetto Uprising monument. The photo went around the world.

crimes trial and executed there in 1952. Ostpolitik under Chancellor Willy Brandt led to a normalisation of German-Polish relations in the early 1970s. During a visit to Warsaw in 1970, Brandt knelt in front of the Ghetto Uprising monument. The photo went around the world.

Edelman turned down job offers from Western clinics and stayed in Poland – even when his wife and children left for the West. Why did he stay in the country? “Somebody has to take care of business here,” he said quietly during our interview in his modest house in Łódź in 1988. “Somehow I owe it to my dead comrades and all those buried down here to stay there.” He died aged 90 on October 2, 2009.

- Die Furche article in original German (DE)

- 01/04/23 AEJ – Tibor Macak on “Revisiting the monsters of Communism”

- 19/04/23 Gazeta Wyborcza, Warsaw Ronald Lauder, leader of World Jewish Congress, on planned extermination of Jews and enslavement of Poles (paywall)

- 18/04/23 Wiener Zeitung Comment by Lauder (DE)

- April, 2013 Die Welt Edelman on Love in the Ghetto