Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his ruling Fidesz party have spent years turning Hungary’s media environment into their playground — not through outright repression, but through market distortion and regulatory capture. Can anything be done?

By Ilya Lozovsky (OCCRP)

This is the question being asked by OCCRP, the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, following the latest attack on the award winning Hungarian investigative news website Átlátszó by a government determined to marginalise all independent media.

The following fake story appeared on 19 news portals at once, each published at exactly 1:46 pm. “Átlátszó journalists receive millions from abroad,” read 19 identical headlines.

Underneath, there were 19 identical texts warning that the investigative media outlet was being funded by enemies of the state.

“Foreign agents’ organisations [like Átlátszó] are working to weaken the Hungarian state,” it read, citing the spokesman of a pro-government NGO. Another quote from its chairman was even more threatening: “The issue should be “examined from the point of view of national security,” he said.

The January 12 fusillade against Átlátszó, an OCCRP member center, was ominous enough. But it’s not what keeps editor-in-chief Tamás Bodoky up at night.

Earlier that week, a right-wing commentator had attacked him in a major pro-government newspaper as a “traitor to the nation.”

Taking umbrage at a reporting project in which Átlátszó had participated — an investigation into how the government spends money to support Hungarians abroad — the writer smeared Bodoky and his fellow independent journalists as “a criminal association of paid agents.”

“This is a very sinister claim,” Bodokoy says. “Because we’re monitoring spending on Hungarian minorities abroad, this makes us enemies of the nation?”

This campaign against a respected independent outlet, known for breaking important stories on corruption, is disturbing in and of itself. But it’s also a disquieting reminder of how far Hungary’s rollback of press freedom has gone.

When the country first joined the EU back in 2003, the European Commission hailed the end of its “tragic separation from the European family of democratic nations.”

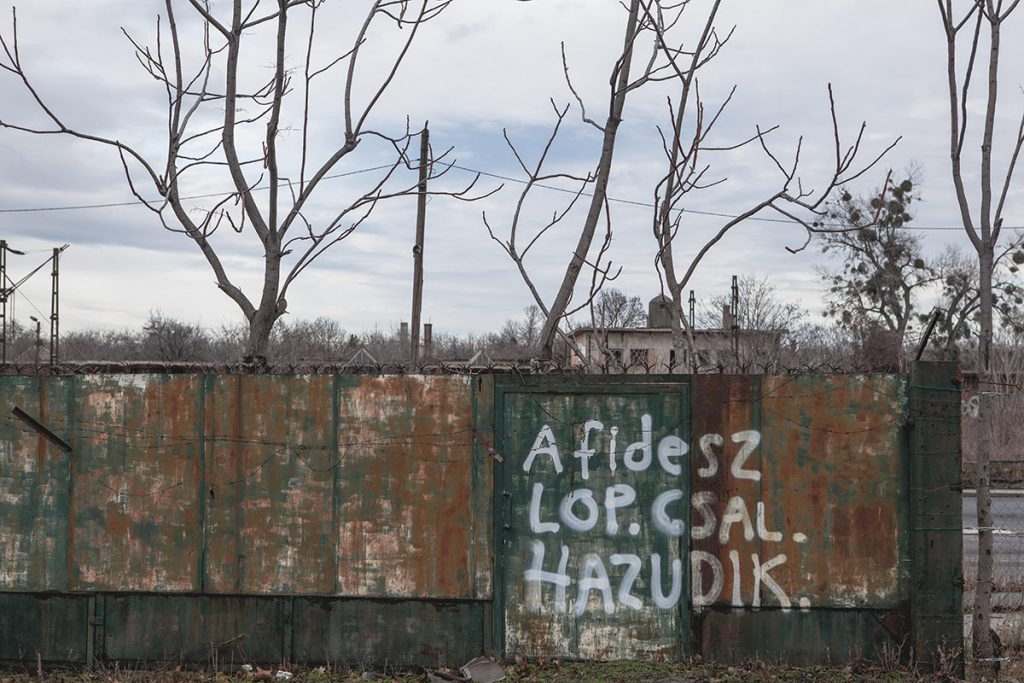

But now the winds in Budapest have taken on a Siberian edge. Under Orbán and his Fidesz party, check after check on government authority has been dismantled or co-opted. The marginalisation of the independent press is one of the most egregious examples.

“Over the past ten years, the situation has changed,” said Dániel Szalay, the editor-in-chief of the independent outlet Media1 and a longtime observer of Hungary’s media scene. “Before, there were many free papers, and many Fidesz papers also. We could choose. There was a mix. And now we’re going into a situation which is similar to Russia.”

“Seventy or eighty percent of the media is under the government, depending on how we calculate,” said Szalay. “[As for] the local papers, the regional papers in the counties — they’re all under Fidesz. The ratio in that case is one hundred percent.”

Achieving such dominance through outright repression, like jailing or exiling troublesome journalists, would be difficult to pull off in a country that’s still nominally a democracy — and would surely raise the alarm in Brussels.

But Orbán has found another way: Distorting Hungary’s once-competitive media market into a caricature where only outlets friendly to the state can thrive.

One way to do this is by capturing the regulators. “If you want to have a radio station,” Szalay says, “the radio frequencies are under the national media authority, and the president of the authority and the members of the media council are elected by Fidesz.”

Even more important is the flow of money.

“After [coming to power in] 2010, Fidesz decided … they would just give [state funding] all to Fidesz-aligned media, and starve everyone else,” Bodoky says. “Since the market follows state spending, left-leaning or socialist-aligned media deteriorated quickly.”

Now “independent outlets are basically restricted to the internet,” he says. “The government only wants those ‘independents’ [to exist] who in reality are on their payroll, and kill any form of financing that enables real independence.”

After years of such practices, the players in Hungary’s media market — which look, at first glance, like the non-profits, business groups, and public broadcasters of any other European country — are all aligned with Fidesz.

And they can easily be directed against the few voices that remain independent, as this winter’s campaign against Átlátszó shows.

The first blow came in December, when the popular news site Origo published a story smearing Átlátszó and several other outlets as leftist enemies “financed by the speculator,” referring to Hungarian-born U.S.-based philanthropist George Soros. The same evening, the story — titled “This is how Soros began to build the Hungarian dollar media” — was amplified on state TV.

Ten years ago, Origo was Hungary’s most prominent independent media outlet. It even published stories embarrassing to Orbán.

But the editorial line changed dramatically after it was acquired in the mid 2010s by a media conglomerate tied to the family of the central bank governor — which was able to make the highest bid in part because it was financed by loans from a state bank.

As the next step, Origo was passed in 2018 into the arms of a new pro-government media foundation.

It wasn’t alone. That November, this media foundation, called KESMA (the Hungarian acronym for “Central European Press and Media Foundation”), was abruptly given a large portion of the country’s media properties by Orbán-friendly business interests, creating what the Associated Press called “a huge right-wing media conglomerate.”

“In just a few hours,” the media freedom group International Press Institute later wrote, “KESMA became the largest media company in Hungary, with hundreds of titles to its name, including a variety of print newspapers and magazines, TV and radio stations, and news websites.”

To forestall any objections from regulators, the government decreed that this consolidation was a matter of “national strategic interest,” exempting it from scrutiny.

Although KESMA is nominally independent, it is led by people close to the ruling party. Its head is Gábor Liszkay, a longtime Orbán loyalist, and its board of trustees has included legislators from Fidesz and the head of a pro-government think tank.

Under their watch, a European fact-finding mission found, KESMA has become a key instrument for “content coordination throughout the pro-government media empire.”

The fruits of that coordination are plain to see in the case of the attacks on Átlátszó: Magyar Nemzet, the newspaper that published the hostile op-eds targeting the outlet, belong to KESMA. So do the 19 sites that published the identical story about Átlátszó last month.

That episode showcases two other weapons in the government’s arsenal: In the first place, the text for those 19 stories was distributed by MTI, the state news agency. Secondly, the story was based entirely on a press conference held earlier that day by the Civic Union Forum, an NGO best known for organizing a series of pro-government marches around the country.

It should come as little surprise that this organization receives state funding — and that the KESMA media outlets do as well.

Such funding is one of the government’s main tactics for tilting the playing field. Unlike independent media outlets, which often struggle to survive financially, pro-Orbán outlets routinely benefit from state advertising campaigns that shove money into their pockets while pushing highly political messages — a strategy Bodoky describes as a “covert way of subsidizing KESMA [outlets] with taxpayer money.”

Mérték, a Hungarian media monitor and think tank, has been submitting detailed complaints to the European Commission on this topic for years. In the most recent report, it found that 86 percent of all state advertising funds in 2020 went to “unequivocally” pro-government outlets.

Where, then, has the EU been?

In the eyes of many observers, the bloc is already guilty of subsidizing Orbán’s anti-democratic turn despite multiplemajor journalistic investigations and years of analysis explaining how his patronage networks exploit incoming European money. For example, a company run by Orbán’s son-in-law received contracts partially funded by the EU to install LED streetlights in Fidesz-run towns across Hungary. In another sector, the government has auctioned vast tracts of state land to Orbán’s’s family members and associates, helping them qualify for EU agricultural subsidies.

“The regime survives and feeds itself by channeling EU funds … into the control of party loyalists and people who support the regime,” said R. Daniel Kelemen, a political scientist at Rutgers University.

“The EU … claims to want to promote democracy both within Europe and around the world. But in fact it has inadvertently become a huge funder of autocracy,” he added. “The EU money has worked like a resource curse, encouraging rent-seeking behavior.”

After years of fruitless legal wrangling, the EU has recently taken the relatively bold step of freezing billions of euros due to the country under several aid mechanisms, citing a host of problems with Hungarian democracy.

With pressure on the budget growing, Orbán’s government has made concessions, including most recently having several ministers resign from university trusts in response to complaints about undue influence.

But Hungarian rights and transparency groups say their country has made little overall progress on rule of law, and experts say any changes will be largely superficial. “We can expert sham reforms,” tweeted Kim Lane Schepperle, a professor of sociology and international affairs at Princeton University. “The only question is whether the [European] Commission will be fooled.”

Regardless of what concessions Brussels is able to extract on democracy, the capture of Hungary’s media landscape is still not even on the agenda. The EU has publicly criticized the Orban government’s approach to a number of important issues, such as rule of law and corruption, academic freedom, refugee policy, and LGBT rights — but has barely mentioned media freedom.

“The media is not part of the deal,” said Szalay. “They know about the problem. … But Brussels is just watching like in a cinema, with popcorn.”

One noteworthy initiative is the European Media Freedom Act, a proposed EU-wide regulation designed to boost transparency of media ownership and combat political interference.

On first glance, legislation meant to address “media capture” seems to be exactly what Hungary needs.

But Agnes Urban, an economist with Mérték, says it won’t be enough.

“It’s very helpful to prevent other countries from going in an illiberal direction,” she says. “But it doesn’t solve the problems of the already-existing illiberal systems like Hungary.”

For example, she says, though the Act would require the directors of public service outlets to be chosen openly, in Hungary “it’s absolutely easy … to manage an open tender in such a way that the pro-government figure will win.”

In addition, though the Act would require EU countries to be transparent in how they award state advertising money, it also says that existing public procurement rules are not affected.

“Probably the thinking is that there’s already transparency in the public procurement process — so, problem solved,” Urban says. But the process in Hungary is problematic, with a large portion of state advertising spending being channeled through a private consortium with informal ties to Fidesz.

“Basically, the secret of the Hungarian illiberal system is in the very small details,” she says. “And it’s not really possible to end these kinds of illiberal practices through this kind of law.”

Given how far things have gone, it’s already difficult to imagine how Orbán’s dominance could be seriously challenged. In the April 2022 elections, his opponents from across the political spectrum united in an unprecedented joint effort to unseat him. The result was a resounding Fidesz victory that even the normally restrained Reuters news agency described as “crushing.”

The leader of the opposition alliance cited the state’s dominance of the media as a key reason for the loss: “We knew this would be an uneven playing field,” he said.

In this environment, Bodoky says, even some of Átlátszó’s hardest-hitting stories have little impact.

“Our reporting does not always reach the audience [because] most mainstream outlets won’t quote or follow-up on politically sensitive or controversial stories,” he says. “We feel marginalized and totally outgunned.”

“One of our former senior reporters is a truck driver now, after reporting for years on the shady businesses of Orban’s son-in-law without any [impact].”

The question is how much more uneven things are going to get. The more durable Orbán’s power, the more levers he will have at his disposal, creating a vicious cycle that’s hard to imagine unwinding. If something is to change, outside actors may have to figure out how to bring pressure to bear.

But Bodoky is still hopeful.

“No autocracy lasts forever,” Bodoky says. “As long as Hungary is a member of the EU and NATO, there’s still a possibility that this will happen in my lifetime.”