Vienna, May 3, 2021

by Walter Hämmerle, Chief Editor, Wiener Zeitung

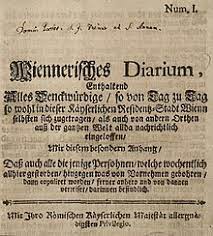

My newspaper, the Wiener Zeitung, is fighting for its life. This is not entirely surprising news. The oldest daily newspaper in the world still being published, it was founded in 1703, then became state property in 1857 thanks to what was deemed “inappropriate behaviour” in the course of the 1848 revolution. It has experienced plenty, revolutions, wars, absolutism, authoritarianism, through fascism to democracy. The full works, in other words, including some situations outside the norm for most media.

When Napoleon occupied Vienna in 1805, for example, and the imperial family fled the city, the French conqueror thought it best to bring along his own editor for the Wiener Zeitung. Later, when the paper was resurrected at the end of 1945, having been discontinued by the Nazis as an unwelcome reminder of an independent Austria, it was a powerful symbol of the new-born Republic.

But today that Republic no longer knows what to do with its own newspaper, whichhas meanwhile developed, almost unintentionally and without a mandate, into a highly-respected quality daily. It just happened, so to speak, but with no clear strategy behind it.

With the digitalisation of the marsupial Amtsblatt (Official Gazette ) whose publishing fees had until now financed the editorial operation, that source of income has also gone. The proprietor, i.e. the Republic, has spent a good decade thinking about new or alternative financing models. All that’s been missing is any political will, let alone imagination, to match a decade of cerebration. And if there’s one thing you must have to ensure the survival of quality journalism, it’s willpower and imagination.

“Nothing to be done about it”

Without these, unfortunately, there’s just nothing anyone can do, as a popular Austrian saying goes. It would be the end of the world’s oldest daily newspaper as a quality medium; what would be left of it would be the brand and “something or other to do with media”.

Let me not be misunderstood: The digitisation of the Amtsbatt, the state-mandated obligations for companies to publish certain official announcements, is right and in truth long overdue. And it is an anomaly for a liberal Western democracy for a newspaper in the – at least indirect – domain of the Federal Chancellery. Compulsory fees as its main source of finance is also an anomaly

It is legitimate to change this. But it also implies a responsibility on the part of the owner to find new answers to the issue of financing. Unless a future is not envisaged at all – or at least not one that is primarily journalistic.

It is hard to imagine what a loss that would mean. After all, Austria’s history and stories of have been reflected in the pages of the Wiener Zeitung for over three centuries. And this has been in unique and – apart from the Nazi period – uninterrupted continuity. What a treasure, what a jewel that threatens to be irretrievably lost! Simply because of a lack of willpower and imagination!

It must be understood at this point that Austria is a strange country when it comes to the media. The course of history and the incessant striving of the powerful to influence what, and how, things are reported have not been able to prevent a self-confident fourth estate from taking its place in the country’s editorial offices.

But independence has recently become precarious again because of the financial crisis and digital disruption. There is hardly a medium here in Austria that could manage without public funding. The very largest, the national TV and radio (ORF), is for the most part financed directly through the collection of a public fee; for most of the others, this is to varying degrees indirectly, through a largely non-transparent allocation of advertising.

What Valhalla might look like

One decisive factor is the underdeveloped willingness of many media consumers to recognise journalism, especially in its qualitative and therefore expensive form, as a product that will inevitably cost a corresponding price. In this country, the saying “he who buys cheap, buys expensive” is especially true because free media are served with a good part of the public advertising pie, which is in turn financed through taxation.

How different the financing of independent quality media would look in an ideal world! The people in their role as citizens of a community would for once actually be the sovereign and hold all the reins in their hands. In this world, people would know about the importance of (quality) journalism for a free and open democracy, and would therefore be prepared to pay the necessary price for this service.

The need to conduct the major debates with an open mind and a fine ear for all necessary voices and arguments would in turn prevent the media from turning into homogeneous loudspeakers of articulate minorities. Audiatur et altera pars, the principle of “let the other side be heard as well,” would not just be obligatory in a court of law, but the supreme principle in all public affairs as well.

The readers, the users in an ideal world, would not perceive such journalism as an imposition on their own convictions, but as something that enriches and expands their horizons, and would therefore not threaten such media with the cancellation of their subscription, but thank them by renewing it for another year. At a price, mind you, that actually has the economic independence of the editorial offices as its goal and purpose. In an ideal world, companies and corporations would incidentally see it the same way and advertise and promote this accordingly.

Unfortunately, the world is not as we want it to be. For Austria, with its nine million inhabitants in a common language area of about 100 million people, this means that quality journalism has no chance of survival without public support. The market of supply and demand does not provide that. It is not a secret. The public sector spends a total of about 1 billion euros on media, all-inclusive. Per year, mind you.

The problem is not the amount, but that there is a lack of comprehensible guidelines and general transparency, especially in the allocation of advertising and cooperation. Yet this criticism is almost as old as the invention of public media. And it is this biotope in which actual and suspected mouse games flourish. Taken as a whole, this is all poison, poison for publishers’ economic independence, which is inseparable from editorial freedom, and poison for a political culture.

The effects of the manifold and utterly contradictory distortions of the Austrian media market are media concentration and the death-knoll for individual newspapers. As of 2021, Austria has only 14 daily newspapers, including the Wiener Zeitung; in Switzerland there are still over 40. Or to put it another way: in Austria there is not too much quality journalism, but too little.

It would be hard to find a better argument for the continued existence of the Wiener Zeitung as a quality newspaper. That is, assuming enough willpower and imagination can be assembled by those concerned.

Public petition to save the paper

Petition to Chancellor Kurz (DE)

Otmar Lahodynsky in the Wiener Zeitung (DE)

Hans Rauscher on why the paper should survive (DE)