by Edward Steen, Vienna May 1 2023

The dictator Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania from 1941 to 1985, had 175,000 steel and concrete bunkers of various sizes built all over his impoverished country until just before his death in 1985.

“Bunkerisation” was supposedly to protect tiny, isolated Albania, the North Korea of its day, from foreign invasion.

In the centre of its capital, Tirana, stands a bunker originally intended only for the Minister of the Interior, head of the dreaded apparatus of state control, whose most visible were the sigurimi secret police.Today the bunker houses an extremely evocative museum devoted to the victims of Communist terror, a period Tibor Macak AEJ Vice-President and Berlin correspondent for Slovak state RSTV, remembers all too vividly from his childhood in what was then Czechoslovakia.

Last weekend Tibor’s recording from the bunker itself was broadcast on Slovak tv:

Tibor Macak: The first song of Asma Asmaton’s Cantata from Mauthausen sounds in the bowels of this bunker – a memento of all the world’s sufferings under totalitarianism. The lyrics, inspired by the biblical Song of Songs, were written by the famous Greek writer Iakovos Kambanellis, who had himself survived the hell of Mauthausen concentration camp. And the ballad is known across the world for the performances of Marie Farantouri.

The labyrinthine nuclear bunker, with 24 rooms, an apartment reserved for the Minister of Internal Affairs and a large hall dedicated to communications, was covered by a 2.5 m- high steel  and concrete ceiling. It was only completed in 1986 – Hoxha did not even live to see its opening, having died the year before, and actully it was never used. (Nor were the others, except by courting couples). After the collapse of the Communist system, the Italian journalist Carlo Bollino proposed that the ministerial bunker was appropriate for a museum dedicated to the victims of Communist terror.

and concrete ceiling. It was only completed in 1986 – Hoxha did not even live to see its opening, having died the year before, and actully it was never used. (Nor were the others, except by courting couples). After the collapse of the Communist system, the Italian journalist Carlo Bollino proposed that the ministerial bunker was appropriate for a museum dedicated to the victims of Communist terror.

As it also included art installations, it was named BunkART. Although its general manager Kristiana Cellei is too young to have ever experienced totalitarianism, she began, in the underground darkness, to tell me fascinating things about the exhibition.

“The bunker served exclusively for the Albanian Ministry of the Interior and was planned in case of war or an atomic attack from abroad. In fact, Enver Hoxha feared that Albania might be attacked not only by the USA, but also by neighbouring Yugoslavia or even the Soviet Union,” she said.

“After the death of Stalin, whom he admired and whose methods of eliminating opponents he consistently used, he gradually broke off relations with Moscow because he rejected Nikita Khrushchev’s criticisms. The bunker covers a much larger area than is open to the public.

“It is a vast labyrinth of corridors under the city centre. The entrance and exit to the bunker were added on the square for museum visitors. Originally, it was only possible to reach the underground from the grounds of the Ministry of the Interior.”

The concrete dome of the bunker’s entrance, next to which stands a guard tower surrounded by barbed wire, attracts attention from far and wide to Tirana. Black-and-white portraits of thousands of victims of wanton terror in the dome’s arch resemble frescoes of people’s faces with specific stories to tell.

“The museum is dedicated to the victims of communism,” she told me. “The exhibition documents the fates of some 5,500 people killed during the totalitarian era. Of course, there are many more, but we have managed to identify these people, and their survivors  have helped us to complete the collection by putting together the exhibits, including photographs.

have helped us to complete the collection by putting together the exhibits, including photographs.

“The portraits in the dome of the bunker above the stairs to the underground are mostly of well-known personalities, but also of ordinary people who were executed by the Hoxha regime.”

A notable aspect of Communist Albania, which Hoxha declared the world’s first atheist state, was its restrictions on foreign visitors.

Kristiana Cellei: “Any foreigner who visited Albania at that time could only stay in one hotel in the centre of Tirana. He had to pass a strict inspection and was not allowed to distinguish his appearance from the rest of the country’s inhabitants.

“If a man had long hair, they cut it off straightaway at the airport. Beards were also forbidden, so on arrival everyone was shaved to look like a normal Albanian.”

A large part of the exhibition covers the activities of the Albanian secret service, the Sigurimi, the equivalent of the Soviet KGB, the Czechoslovak StB, or the East German STASI. It belonged to the Ministry of the Interior and its methods were feared even by the top leaders of the Albanian Labour Party because it eliminated any hint of resistance to the Hoxha Doctrine.

It also executed some 170 members of the party’s Central Committee who had fallen into disfavour, including ministers of the Interior. Their portraits hang on the wall of a room that differs greatly from the others.

“This was one of the most important rooms of the bunker and belonged to the Minister of the Interior,” said Kristiana. “It had the best technical equipment for the time, and every member of his staff could sit at the large table. There was the first computer in Albania, as well as a large radio and a colour television.”

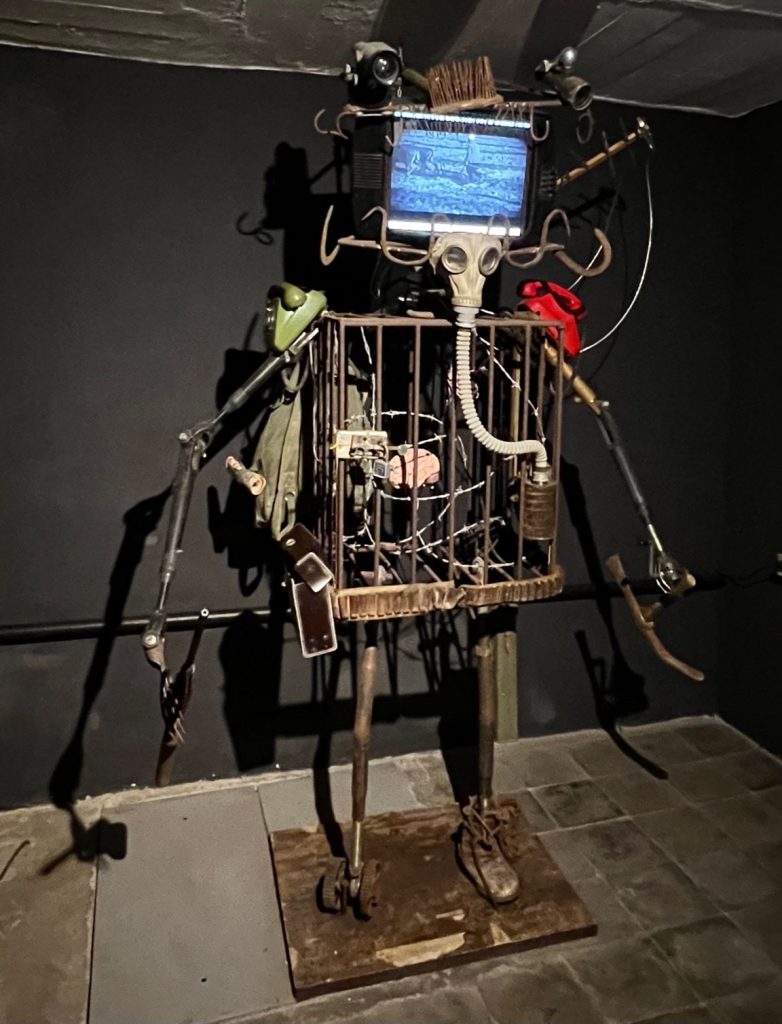

Also on display are the tools of media propaganda, for controlling public opinion, manipulation of photographs and film material. One of the art installations inspired by the totalitarian system is the Monster of Communism by the Albanian artist Rajmod Zaymi Avignon.

“In one hand he has a rifle, in the other a pickaxe, symbolizing the working class,” explained Kristiana Cellei. “The heart and brain are encased in a steel cage chest, which also contains barbed wire, suggesting imprisonment and control by Communist power.

“The cage is hung with telephones, tapped by the secret service. The head of the monster is a monitor, with security cameras and a gas mask on it.

“A black-and-white film of totalitarian propaganda runs on the screen, and at the end of the film, the artist’s message appears: ‘If one day you decide to fight the monsters, remember what you are trying to do. And always be careful of the monster inside you, too.'”

Another message, written on the wall of one of the museum’s rooms, is also related to the monster of Communism. Its author is Mother Teresa, who is held in high esteem in Muslim Albania and also considered a saint by Moslems.

Although born to a Catholic family in Skopje, northern Macedonia, her father was Albanian and her mother was from Kosovo. Mother Teresa’s message is clear: “Evil takes root when a person begins to think he is better than others.”

Tirana’s Museum of the Victims of Communism contains plenty of evidence that Mother Teresa was right about that.

- 03/04/23 AEJ Memories of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 1943 – Lahodynsky interview with late Dr Marek Edelman. In original German/ DE