by Yasmeen Serhan, The Atlantic, March 22, 2022

As Russian forces continue their brutal invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin is waging a digital war of his own at home. Russia’s media sphere, which was tightly controlled by the state even before the Ukraine invasion, has become even smaller.

For years, Putin has overseen a sustained crackdown on press freedom in Russia—a process that in recent weeks claimed two of the country’s last remaining independent news broadcasters, TV Rain and Echo of Moscow. Now, thanks to the Kremlin’s latest censorship law, many of the West’s major news outlets have been forced out of the country too, and millions of Russians find themselves blocked from accessing numerous major social-media platforms as well as anything resembling free and independent news.

Instead of giving up on their Russian audiences, though, international news organizations are trying to exploit gaps within this new digital iron curtain to reach the Russian people.

Although the majority of Russians rely on state-run television as their primary source of news, the fact that some consume news from foreign outlets has long upset the Russian government, which has spent years asserting control over domestic and foreign media in the country.

But even by the Kremlin’s standards, this latest effort to block Russians from much of the internet marks an escalation—one that has quickly transformed the country into a digital pariah. Russians are, however, finding technical workarounds to sidestep the government’s bans, some of which have been encouraged by international news outlets that are keen to maintain a digital presence in the country, even if they can no longer claim a physical one. The New York Times, which has announced that it has withdrawn its journalists from Russia, and The Washington Post, which has removed bylines from its Russia stories to prevent its journalists there from being caught up in the crackdown, launched their own dedicated channels on Telegram, the as-yet-unbanned social-media-and-messaging app that claims more than 1 billion downloads (Russia is its second-biggest market) and acts as a platform to both news outlets and Russian state channels alike.

Russians are, however, finding technical workarounds to sidestep the government’s bans, some of which have been encouraged by international news outlets that are keen to maintain a digital presence in the country, even if they can no longer claim a physical one. The New York Times, which has announced that it has withdrawn its journalists from Russia, and The Washington Post, which has removed bylines from its Russia stories to prevent its journalists there from being caught up in the crackdown, launched their own dedicated channels on Telegram, the as-yet-unbanned social-media-and-messaging app that claims more than 1 billion downloads (Russia is its second-biggest market) and acts as a platform to both news outlets and Russian state channels alike.

Meanwhile, the BBC, whose Russian-language website more than tripled its weekly average audience (10.7 million people compared with its average 3.1 million) in the first week of the Russian invasion, before being blocked by the Kremlin, encouraged its audience to use tools such as the Psiphon app, an open-source, virtual private-network service that helps users conceal their location, and Tor, a more secure web browser. (The British broadcaster also reverted to more old-school tactics, announcing that it would revive its shortwave radio service as an alternative means of reaching its audiences in Ukraine and Russia.)

In the weeks since the Russian invasion began, demand for VPNs in the country has skyrocketed by more than 2,500 percent compared with pre-invasion levels, according to Top10VPN, an online VPN tracker.

Perhaps no outlet is better placed to overcome these challenges than Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. The broadcaster was founded during the Cold War with the explicit purpose of reaching audiences behind the Iron Curtain. Despite the Soviet Union’s efforts to jam broadcasts, “people still found a way through the static,” Jamie Fly, the president of RFE/RL, told me. “I meet people all the time who remember sitting by the radio, literally turning the dial, trying to find the one frequency that had not been jammed.” Today, RFE/RL, which is funded by (though editorially independent from) the United States government, is directing its audience to utilize a number of circumvention tools, including VPNs and Telegram.

I spoke with Fly days after RFE/RL announced that it was suspending its operations in Russia after a more-than-three-decade presence in the country (initiated in 1991 with an invitation from then–Russian President Boris Yeltsin to open a permanent bureau in Moscow, which Putin revoked a decade later). The decision, which came days after the Russian government blocked access to RFE/RL and several other foreign broadcasters, was the culmination of the Kremlin’s yearslong campaign to expel the broadcaster—one that involved designating RFE/RL as a “foreign agent” and subjecting it to tens of millions of dollars in fines. Although the broadcaster continues to report from within Russia “in a limited fashion,” Fly said that the majority of its Russian service is now based out of Riga, in neighbouring Latvia.

That RFE/RL now finds itself facing another iron curtain, with its primary methods of serving its audience once again jammed by authorities who would much rather it didn’t exist, hasn’t undermined its resolve. “Our history is coming full circle,” Kiryl Sukhotski, who oversees RFE/RL’s Russian and Ukrainian teams, told me. Only this time, the broadcaster has more technological tools in its arsenal. In addition to Telegram and VPNs, RFE/RL has also been experimenting with other circumvention tools such as mirror sites, which enable the outlet to replicate or “mirror” the content from its blocked website at a different URL. When those sites invariably get blocked, “we just open up a new mirror,” Patrick Boehler, RFE/RL’s head of digital strategy, told me. “It’s a bit of a cat-and-mouse game.”

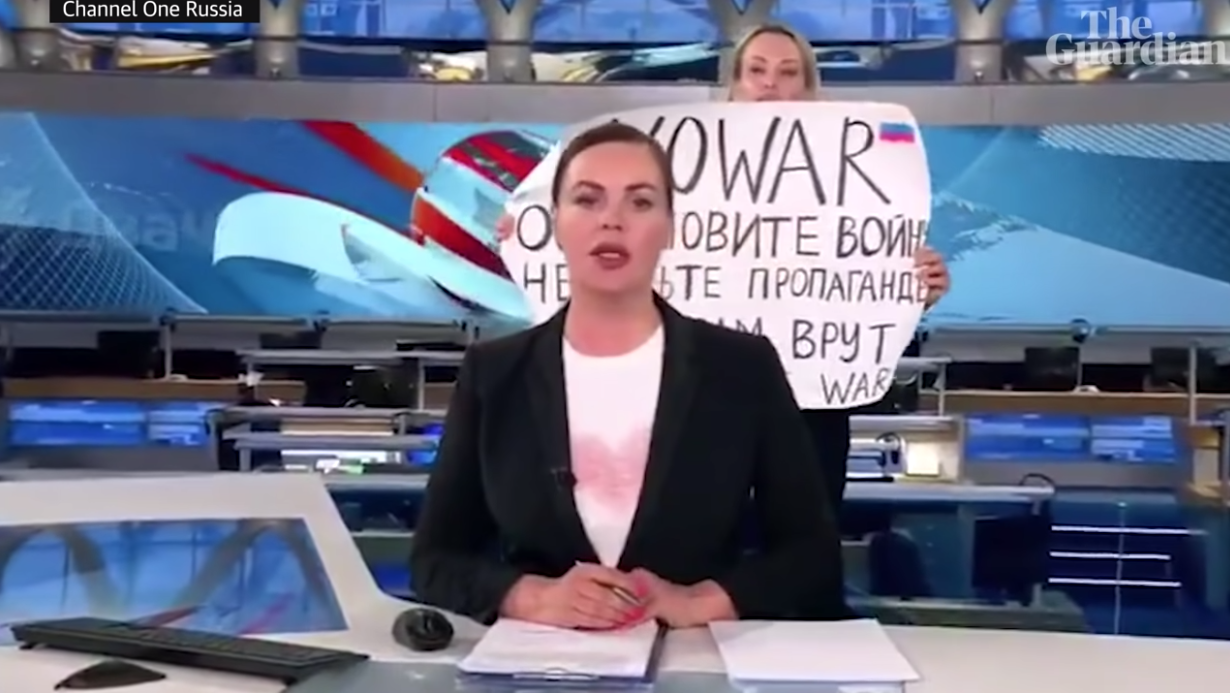

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing the broadcaster isn’t getting its content to Russian audiences but ensuring that its methods are easily accessible. This is where the Kremlin has the greatest advantage. For all the Russians who have been able to access independent news and information using various circumvention tools, millions more remain firmly ensconced within the Kremlin’s echo chamber. (The rare exception was the brave anti-war interruption of the main Channel 1 evening news on March 14. ES)

Although its influence in Russia has been in decline, state-run television still remains the primary source of news for as much as 62 percent of Russians, according to a 2021 study by the Moscow-based Levada Center, Russia’s last independent pollster. To tune in to a typical Russian television broadcast, as my colleague Olga Khazan recently did, is to peek into this carefully crafted alternate reality—one in which Russia is the victim, the Ukrainian government is controlled by Nazis, and the war in Ukraine doesn’t exist.

“If you’re a middle-aged person who is not really on the internet, who is maybe supportive of Putin and the government, and you’re watching TV, as most Russians of that age do, you will definitely be exposed  to a firehose of propaganda about how bad the West is and [how] Russians are under attack,” Jill Dougherty (right), an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and CNN’s former Moscow bureau chief, told me.

to a firehose of propaganda about how bad the West is and [how] Russians are under attack,” Jill Dougherty (right), an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and CNN’s former Moscow bureau chief, told me.

The pervasive nature of the Russian government’s efforts doesn’t make attempts to combat them any less vital, however. “Even if a Russian thought that it was propaganda from the West, at least they’re getting a different viewpoint,” Dougherty said. “What they’re getting right now is only one viewpoint, and it is highly emotional and very angry.”

Though news outlets such as RFE/RL are best placed to provide these alternative viewpoints, they aren’t the only ones who can. Former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger made an impassioned appeal to Russian citizens through Telegram and other channels, urging them to spread the truth about what is happening in Ukraine. Others have endeavored to reach out to ordinary Russians directly using a tool created by a team of Polish programmers known as Squad303 that enables anyone to text, email, or phone tens of millions of Russians at random. Since its March 4 launch, thousands of people have used the service to send more than 40 million messages to Russians directly with information about the war. “We are bypassing the digital iron curtain,” a Squad303 spokesperson told me. He cited RFE/RL as part of the group’s inspiration.

“Thanks to Radio Free Europe, there was in us a hunger for freedom and democracy, which was the basis for the creation of Solidarity, which in effect overthrew communism in Europe,” he said, referencing the independent Polish trade union. “Now we are trying to help the Russian people in the same way.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger: I have a message for my Russian friends

The way everyone I spoke with for this story sees it, the West—and, in particular, its news media—has an obligation not to turn its back on the Russian public. As space for alternative information becomes ever smaller, and as the threats against those who diverge from the Kremlin’s narrative become more explicit, the greater that responsibility becomes.

Yasmeen Serhan is a London-based staff writer at The Atlantic.