Vienna, November 27, 2021

by Otmar Lahodynsky, honorary AEJ President

The stroke of a pen in a snow-bound forest in Belorussia changed the world

On December 8, 1991, the leaders of the three main Soviet republics met at a state-run country hotel and officially dissolved the Communist state. The elderly gentlemen who came to Vienna were visibly emotional as they remembered the signing of the treaty that dissolved the USSR in December 1991, exactly 30 years ago.

Four of the surviving signatories of the “Agreement Establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States” met again at Vienna’s Diplomatic Academy on November 17. They recounted exactly what happened at a state-run country house in a forest in Belarussia almost exactly 30 years ago.

Four of the surviving signatories of the “Agreement Establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States” met again at Vienna’s Diplomatic Academy on November 17. They recounted exactly what happened at a state-run country house in a forest in Belarussia almost exactly 30 years ago.

The agreement, initially signed by Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine was not planned by the participants. In fact, there wasn’t even an agenda. The Belarussian contingent had come to discuss energy supplies from Russia, said Stanislav Shushkevich, independent Belarus’ first president.

Along with the other leaders present – Russia’s Boris Yeltsin, Leonid Kravchuk from Ukraine – had already, before the meeting, agreed that the USSR no longer existed. What was still missing, however, was only a de jure dissolution treaty.

So what happened in that snowy hotel in the forest was neither a form of treason nor conspiracy, for former Ukrainian Prime Minister Vitold Fokin, now 89. “We went there thinking of our homeland and its welfare,” he said. But shortly before there had been pressure from then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to sign a new union alliance that would allow the USSR to continue, albeit with a new structure.

“It occurred to me that Ukraine had a real chance of becoming an independent and sovereign state,” Fokin said, though the death of the Soviet Union “of course” saddened him.

ALCOHOL “NOT TO BLAME”

Fokin also denied a rumoUr that the three politicians had decided the fate of a world power while intoxicated. They were fully focussed,” he insisted. “Of course, after a hard day’s work, we also drank whisky and vodka. But we were 30 years younger then.” And next morning “everyone was completely sober again.“

The then-Russian Deputy Prime Minister Gennady Burbulis, who co-signed the agreement for Russia with Yeltsin, spoke of the central role that Ukraine played in ending the Soviet Union. In presidential elections and a referendum on December 1, 1991, in which 90 per cent of the Ukrainian population supported their country’s independence, Ukraine received a “resounding legitimacy for its centuries-long quest for sovereignty,” Burbulis stressed.

Before the trip to Belovezh, Yeltsin had assured Soviet President Gorbachev that he was in favouar of a renewed Soviet Union, but that the Ukrainians had publicly declared that this was not possible. “Ukrainian President Kravchuk said that he did not know where the Kremlin was and who Gorbachev was supposed to be. By declaring independence, the Ukrainians had also ruled out any kind of confederation. Against this background, the three finally agreed to establish a commonwealth of ex-Soviet republics, Burbulis explained, who added that at that time the talk was of future cooperation without obligations, one that was based on friendship and trust.

Despite the Ukrainian position, Yeltsin was the driving force behind the agreement of December 8, as former Belorussian Foreign Minister Pyotr Kravchenko said. His Russian counterpart at the time, Andrey Kozyrev, a close comrade-in-arms of Yeltsin, had told him about the planned agreement on December 7 while on the plane to Belarus. It had surprised him.

A text of the agreement was then drafted on the night of December 8. Kravchenko also noted that the Ukrainian delegation had only claimed one change in the agreement. The Ukrainians wanted the text to alter a reference to a “community of democratic states” in favour of “independent”, instead of “democratic”, in order to connect the soon-to-signed declaration with Ukraine’s independence referendum.

One participant was astonished to hear that the agreement had already provided for the transfer of nuclear weapons from Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan to the Russian Federation, which had already declared itself as the legal successor to the Soviet Union. At the time, the preamble also agreed on mutual respect for the territorial integrity of the new states.

This had ensured a largely peaceful end to the Soviet state, a rare occurrence in the history of the disintegration of empires. Shortly after the Belovezh Accords were signed, the dissolution of Yugoslavia led to a series of bloody wars in the heart of Europe that left tens of thousands dead.

Certainly, the signers of the Belovezh Accords were not at first aware that a major event in world history was taking place in a snow-covered Belorussian forest. When they heard the Soviet anthem on the radio the next morning, tears were shed. For despite all its mistakes, the Soviet Union had been “a great state” for whose well-being Yeltsin, Kravchuk, and Shushkevich had gladly worked.

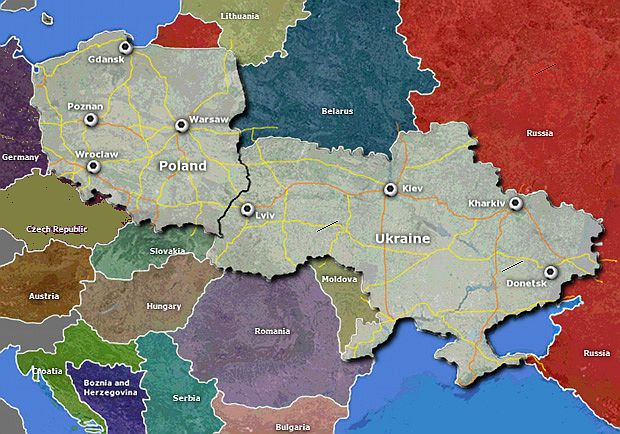

The Soviet Union had also been a counterweight to the other world powers, above all the United States. Shortly after the meeting in the Belovezh Forest, the Soviet Union disappeared from the map and 15 new states emerged.

Soviet President Gorbachev, who had tried desperately for months to save the Soviet Union in a renewed form, resigned on December 25, 1991, and the Soviet red flag, with the hammer and sickle over the Kremlin, was taken down.

The author of this article was a correspondent in Brussels at the time. In mid-December 1991, a meeting of NATO foreign ministers took place in Brussels. As had been the case for some time, the representatives of the countries of the Partnership for Peace were invited, including the ambassador of the Soviet Union. He read out a letter from Yeltsin in which he held out the prospect of cooperation with the Western alliance, which could later even include membership for Russia.

Afterwards, the ambassador asked to remove all symbols of the faded Soviet Union and to hoist the new flag of the Russian Federation, for which he was now the ambassador. This was not entirely possible, however, but NATO officials hurriedly took down the red flag of the Soviet Union from its flagpole.

In 2008, Vladimir Putin described the dissolution of the Soviet Union as the “greatest catastrophe of the 20th century”. He later said his one political wish would be to bring the Soviet Union back into existence if it were possible.

That idea, 30 years ago, would have been the furthest from the minds of the three men who put the final nail in the coffin of the Soviet experiment. It is truly incredible how much things have changed in one generation.

Link: Lahodynsky article published in New Europe, Brussels